«Intel 64» redirects here. For the Intel 64-bit architecture in Itanium chips, see IA-64.

x86-64 (also known as x64, x86_64, AMD64, and Intel 64)[note 1] is a 64-bit version of the x86 instruction set, first released in 1999. It introduced two new modes of operation, 64-bit mode and compatibility mode, along with a new 4-level paging mode.

With 64-bit mode and the new paging mode, it supports vastly larger amounts of virtual memory and physical memory than was possible on its 32-bit predecessors, allowing programs to store larger amounts of data in memory. x86-64 also expands general-purpose registers to 64-bit, and expands the number of them from 8 (some of which had limited or fixed functionality, e.g. for stack management) to 16 (fully general), and provides numerous other enhancements. Floating-point arithmetic is supported via mandatory SSE2-like instructions, and x87/MMX style registers are generally not used (but still available even in 64-bit mode); instead, a set of 16 vector registers, 128 bits each, is used. (Each register can store one or two double-precision numbers or one to four single-precision numbers, or various integer formats.) In 64-bit mode, instructions are modified to support 64-bit operands and 64-bit addressing mode.

The compatibility mode defined in the architecture allows 16- and 32-bit user applications to run unmodified, coexisting with 64-bit applications if the 64-bit operating system supports them.[11][note 2] As the full x86 16-bit and 32-bit instruction sets remain implemented in hardware without any intervening emulation, these older executables can run with little or no performance penalty,[13] while newer or modified applications can take advantage of new features of the processor design to achieve performance improvements. Also, a processor supporting x86-64 still powers on in real mode for full backward compatibility with the 8086, as x86 processors supporting protected mode have done since the 80286.

The original specification, created by AMD and released in 2000, has been implemented by AMD, Intel, and VIA. The AMD K8 microarchitecture, in the Opteron and Athlon 64 processors, was the first to implement it. This was the first significant addition to the x86 architecture designed by a company other than Intel. Intel was forced to follow suit and introduced a modified NetBurst family which was software-compatible with AMD’s specification. VIA Technologies introduced x86-64 in their VIA Isaiah architecture, with the VIA Nano.

The x86-64 architecture was quickly adopted for desktop and laptop personal computers and servers which were commonly configured for 16GB of memory or more. It has effectively replaced the discontinued Intel Itanium architecture (formerly IA-64), which was originally intended to replace the x86 architecture. x86-64 and Itanium are not compatible on the native instruction set level, and operating systems and applications compiled for one architecture cannot be run on the other.

AMD64[edit]

History[edit]

AMD64 (also variously referred to by AMD in their literature and documentation as “AMD 64-bit Technology” and “AMD x86-64 Architecture”) was created as an alternative to the radically different IA-64 architecture designed by Intel and Hewlett-Packard, which was backward-incompatible with IA-32, the 32-bit version of the x86 architecture. AMD originally announced AMD64 in 1999[14] with a full specification available in August 2000.[15] As AMD was never invited to be a contributing party for the IA-64 architecture and any kind of licensing seemed unlikely, the AMD64 architecture was positioned by AMD from the beginning as an evolutionary way to add 64-bit computing capabilities to the existing x86 architecture while supporting legacy 32-bit x86 code, as opposed to Intel’s approach of creating an entirely new, completely x86-incompatible 64-bit architecture with IA-64.

The first AMD64-based processor, the Opteron, was released in April 2003.

Implementations[edit]

AMD’s processors implementing the AMD64 architecture include Opteron, Athlon 64, Athlon 64 X2, Athlon 64 FX, Athlon II (followed by «X2», «X3», or «X4» to indicate the number of cores, and XLT models), Turion 64, Turion 64 X2, Sempron («Palermo» E6 stepping and all «Manila» models), Phenom (followed by «X3» or «X4» to indicate the number of cores), Phenom II (followed by «X2», «X3», «X4» or «X6» to indicate the number of cores), FX, Fusion/APU and Ryzen/Epyc.[citation needed]

Architectural features[edit]

The primary defining characteristic of AMD64 is the availability of 64-bit general-purpose processor registers (for example, rax), 64-bit integer arithmetic and logical operations, and 64-bit virtual addresses.[citation needed]

The designers took the opportunity to make other improvements as well.

Notable changes in the 64-bit extensions include:

- 64-bit integer capability

- All general-purpose registers (GPRs) are expanded from 32 bits to 64 bits, and all arithmetic and logical operations, memory-to-register and register-to-memory operations, etc., can operate directly on 64-bit integers. Pushes and pops on the stack default to 8-byte strides, and pointers are 8 bytes wide.

- Additional registers

- In addition to increasing the size of the general-purpose registers, the number of named general-purpose registers is increased from eight (i.e. eax, ecx, edx, ebx, esp, ebp, esi, edi) in x86 to 16 (i.e. rax, rcx, rdx, rbx, rsp, rbp, rsi, rdi, r8, r9, r10, r11, r12, r13, r14, r15). It is therefore possible to keep more local variables in registers rather than on the stack, and to let registers hold frequently accessed constants; arguments for small and fast subroutines may also be passed in registers to a greater extent.

- AMD64 still has fewer registers than many RISC instruction sets (e.g. PA-RISC, Power ISA, and MIPS have 32 GPRs; Alpha, 64-bit ARM, and SPARC have 31) or VLIW-like machines such as the IA-64 (which has 128 registers). However, an AMD64 implementation may have far more internal registers than the number of architectural registers exposed by the instruction set (see register renaming). (For example, AMD Zen cores have 168 64-bit integer and 160 128-bit vector floating-point physical internal registers.)

- Additional XMM (SSE) registers

- Similarly, the number of 128-bit XMM registers (used for Streaming SIMD instructions) is also increased from 8 to 16.

- The traditional x87 FPU register stack is not included in the register file size extension in 64-bit mode, compared with the XMM registers used by SSE2, which did get extended. The x87 register stack is not a simple register file although it does allow direct access to individual registers by low cost exchange operations.

- Larger virtual address space

- The AMD64 architecture defines a 64-bit virtual address format, of which the low-order 48 bits are used in current implementations.[11]: 120 This allows up to 256 TB (248 bytes) of virtual address space. The architecture definition allows this limit to be raised in future implementations to the full 64 bits,[11]: 2 : 3 : 13 : 117 : 120 extending the virtual address space to 16 EB (264 bytes).[16] This is compared to just 4 GB (232 bytes) for the x86.[17]

- This means that very large files can be operated on by mapping the entire file into the process’s address space (which is often much faster than working with file read/write calls), rather than having to map regions of the file into and out of the address space.

- Larger physical address space

- The original implementation of the AMD64 architecture implemented 40-bit physical addresses and so could address up to 1 TB (240 bytes) of RAM.[11]: 24 Current implementations of the AMD64 architecture (starting from AMD 10h microarchitecture) extend this to 48-bit physical addresses[18] and therefore can address up to 256 TB (248 bytes) of RAM. The architecture permits extending this to 52 bits in the future[11]: 24 [19] (limited by the page table entry format);[11]: 131 this would allow addressing of up to 4 PB of RAM. For comparison, 32-bit x86 processors are limited to 64 GB of RAM in Physical Address Extension (PAE) mode,[20] or 4 GB of RAM without PAE mode.[11]: 4

- Larger physical address space in legacy mode

- When operating in legacy mode the AMD64 architecture supports Physical Address Extension (PAE) mode, as do most current x86 processors, but AMD64 extends PAE from 36 bits to an architectural limit of 52 bits of physical address. Any implementation, therefore, allows the same physical address limit as under long mode.[11]: 24

- Instruction pointer relative data access

- Instructions can now reference data relative to the instruction pointer (RIP register). This makes position-independent code, as is often used in shared libraries and code loaded at run time, more efficient.

- SSE instructions

- The original AMD64 architecture adopted Intel’s SSE and SSE2 as core instructions. These instruction sets provide a vector supplement to the scalar x87 FPU, for the single-precision and double-precision data types. SSE2 also offers integer vector operations, for data types ranging from 8bit to 64bit precision. This makes the vector capabilities of the architecture on par with those of the most advanced x86 processors of its time. These instructions can also be used in 32-bit mode. The proliferation of 64-bit processors has made these vector capabilities ubiquitous in home computers, allowing the improvement of the standards of 32-bit applications. The 32-bit edition of Windows 8, for example, requires the presence of SSE2 instructions.[21] SSE3 instructions and later Streaming SIMD Extensions instruction sets are not standard features of the architecture.

- No-Execute bit

- The No-Execute bit or NX bit (bit 63 of the page table entry) allows the operating system to specify which pages of virtual address space can contain executable code and which cannot. An attempt to execute code from a page tagged «no execute» will result in a memory access violation, similar to an attempt to write to a read-only page. This should make it more difficult for malicious code to take control of the system via «buffer overrun» or «unchecked buffer» attacks. A similar feature has been available on x86 processors since the 80286 as an attribute of segment descriptors; however, this works only on an entire segment at a time.

- Segmented addressing has long been considered an obsolete mode of operation, and all current PC operating systems in effect bypass it, setting all segments to a base address of zero and (in their 32-bit implementation) a size of 4 GB. AMD was the first x86-family vendor to implement no-execute in linear addressing mode. The feature is also available in legacy mode on AMD64 processors, and recent Intel x86 processors, when PAE is used.

- Removal of older features

- A few «system programming» features of the x86 architecture were either unused or underused in modern operating systems and are either not available on AMD64 in long (64-bit and compatibility) mode, or exist only in limited form. These include segmented addressing (although the FS and GS segments are retained in vestigial form for use as extra-base pointers to operating system structures),[11]: 70 the task state switch mechanism, and virtual 8086 mode. These features remain fully implemented in «legacy mode», allowing these processors to run 32-bit and 16-bit operating systems without modifications. Some instructions that proved to be rarely useful are not supported in 64-bit mode, including saving/restoring of segment registers on the stack, saving/restoring of all registers (PUSHA/POPA), decimal arithmetic, BOUND and INTO instructions, and «far» jumps and calls with immediate operands.

Virtual address space details[edit]

Canonical form addresses[edit]

Current 48-bit implementation

57-bit implementation

64-bit implementation

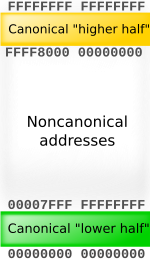

Although virtual addresses are 64 bits wide in 64-bit mode, current implementations (and all chips that are known to be in the planning stages) do not allow the entire virtual address space of 264 bytes (16 EB) to be used. This would be approximately four billion times the size of the virtual address space on 32-bit machines. Most operating systems and applications will not need such a large address space for the foreseeable future, so implementing such wide virtual addresses would simply increase the complexity and cost of address translation with no real benefit. AMD, therefore, decided that, in the first implementations of the architecture, only the least significant 48 bits of a virtual address would actually be used in address translation (page table lookup).[11]: 120

In addition, the AMD specification requires that the most significant 16 bits of any virtual address, bits 48 through 63, must be copies of bit 47 (in a manner akin to sign extension). If this requirement is not met, the processor will raise an exception.[11]: 131 Addresses complying with this rule are referred to as «canonical form.»[11]: 130 Canonical form addresses run from 0 through 00007FFF’FFFFFFFF, and from FFFF8000’00000000 through FFFFFFFF’FFFFFFFF, for a total of 256 TB of usable virtual address space. This is still 65,536 times larger than the virtual 4 GB address space of 32-bit machines.

This feature eases later scalability to true 64-bit addressing. Many operating systems (including, but not limited to, the Windows NT family) take the higher-addressed half of the address space (named kernel space) for themselves and leave the lower-addressed half (user space) for application code, user mode stacks, heaps, and other data regions.[22] The «canonical address» design ensures that every AMD64 compliant implementation has, in effect, two memory halves: the lower half starts at 00000000’00000000 and «grows upwards» as more virtual address bits become available, while the higher half is «docked» to the top of the address space and grows downwards. Also, enforcing the «canonical form» of addresses by checking the unused address bits prevents their use by the operating system in tagged pointers as flags, privilege markers, etc., as such use could become problematic when the architecture is extended to implement more virtual address bits.

The first versions of Windows for x64 did not even use the full 256 TB; they were restricted to just 8 TB of user space and 8 TB of kernel space.[22] Windows did not support the entire 48-bit address space until Windows 8.1, which was released in October 2013.[22]

Page table structure[edit]

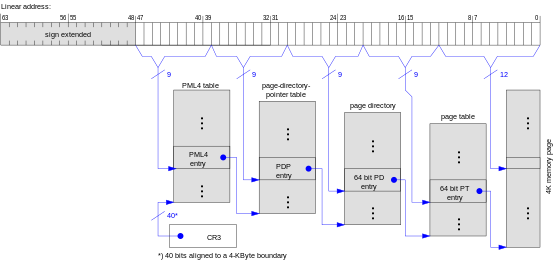

The 64-bit addressing mode («long mode») is a superset of Physical Address Extensions (PAE); because of this, page sizes may be 4 KB (212 bytes) or 2 MB (221 bytes).[11]: 120 Long mode also supports page sizes of 1 GB (230 bytes).[11]: 120 Rather than the three-level page table system used by systems in PAE mode, systems running in long mode use four levels of page table: PAE’s Page-Directory Pointer Table is extended from four entries to 512, and an additional Page-Map Level 4 (PML4) Table is added, containing 512 entries in 48-bit implementations.[11]: 131 A full mapping hierarchy of 4 KB pages for the whole 48-bit space would take a bit more than 512 GB of memory (about 0.195% of the 256 TB virtual space).

-

64 bit page table entry

Bits: 63 62 … 52 51 … 32 Content: NX reserved Bit 51…32 of base address Bits: 31 … 12 11 … 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Content: Bit 31…12 of base address ign. G PAT D A PCD PWT U/S R/W P

Intel has implemented a scheme with a 5-level page table, which allows Intel 64 processors to support a 57-bit virtual address space.[23] Further extensions may allow full 64-bit virtual address space and physical memory by expanding the page table entry size to 128-bit, and reduce page walks in the 5-level hierarchy by using a larger 64 KB page allocation size that still supports 4 KB page operations for backward compatibility.[24]

Operating system limits[edit]

The operating system can also limit the virtual address space. Details, where applicable, are given in the «Operating system compatibility and characteristics» section.

Physical address space details[edit]

Current AMD64 processors support a physical address space of up to 248 bytes of RAM, or 256 TB.[18] However, as of 2020, there were no known x86-64 motherboards that support 256 TB of RAM.[25][26][27][28][failed verification] The operating system may place additional limits on the amount of RAM that is usable or supported. Details on this point are given in the «Operating system compatibility and characteristics» section of this article.

Operating modes[edit]

The architecture has two primary modes of operation: long mode and legacy mode.

| Operating | Operating system required | Type of code being run | Size (in bits) | No. of general-purpose registers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mode | sub-mode | addresses | operands (default in italics) | |||

| Long mode | 64-bit mode | 64-bit OS, 64-bit UEFI firmware, or the previous two interacting via a 64-bit firmware’s UEFI interface | 64-bit | 64 | 8, 16, 32, 64 | 16 |

| Compatibility mode | Bootloader or 64-bit OS | 32-bit | 32 | 8, 16, 32 | 8 | |

| 16-bit protected mode | 16 | 8, 16, 32 | 8 | |||

| Legacy mode | Protected mode | Bootloader, 32-bit OS, 32-bit UEFI firmware, or the latter two interacting via the firmware’s UEFI interface | 32-bit | 32 | 8, 16, 32 | 8 |

| 16-bit protected mode OS | 16-bit protected mode | 16 | 8, 16, 32[m 1] | 8 | ||

| Virtual 8086 mode | 16-bit protected mode or 32-bit OS | subset of real mode | 16 | 8, 16, 32[m 1] | 8 | |

| Unreal mode | Bootloader or real mode OS | real mode | 16, 20, 32 | 8, 16, 32[m 1] | 8 | |

| Real mode | Bootloader, real mode OS, or any OS interfacing with a firmware’s BIOS interface[29] | real mode | 16, 20, 21 | 8, 16, 32[m 1] | 8 |

- ^ a b c d Note that 16-bit code written for the 80286 and below does not use 32-bit operand instructions. Code written for the 80386 and above can use the operand-size override prefix (0x66). Normally this prefix is used by protected and long mode code for the purpose of using 16-bit operands, as that code would be running in a code segment with a default operand size of 32 bits. In real mode, the default operand size is 16 bits, so the 0x66 prefix is interpreted differently, changing operand size to 32 bits.

Long mode[edit]

Long mode is the architecture’s intended primary mode of operation; it is a combination of the processor’s native 64-bit mode and a combined 32-bit and 16-bit compatibility mode. It is used by 64-bit operating systems. Under a 64-bit operating system, 64-bit programs run under 64-bit mode, and 32-bit and 16-bit protected mode applications (that do not need to use either real mode or virtual 8086 mode in order to execute at any time) run under compatibility mode. Real-mode programs and programs that use virtual 8086 mode at any time cannot be run in long mode unless those modes are emulated in software.[11]: 11 However, such programs may be started from an operating system running in long mode on processors supporting VT-x or AMD-V by creating a virtual processor running in the desired mode.

Since the basic instruction set is the same, there is almost no performance penalty for executing protected mode x86 code. This is unlike Intel’s IA-64, where differences in the underlying instruction set mean that running 32-bit code must be done either in emulation of x86 (making the process slower) or with a dedicated x86 coprocessor. However, on the x86-64 platform, many x86 applications could benefit from a 64-bit recompile, due to the additional registers in 64-bit code and guaranteed SSE2-based FPU support, which a compiler can use for optimization. However, applications that regularly handle integers wider than 32 bits, such as cryptographic algorithms, will need a rewrite of the code handling the huge integers in order to take advantage of the 64-bit registers.

Legacy mode[edit]

Legacy mode is the mode that the processor is in when it is not in long mode.[11]: 14 In this mode, the processor acts like an older x86 processor, and only 16-bit and 32-bit code can be executed. Legacy mode allows for a maximum of 32 bit virtual addressing which limits the virtual address space to 4 GB.[11]: 14 : 24 : 118 64-bit programs cannot be run from legacy mode.

Protected mode[edit]

Protected mode is made into a submode of legacy mode.[11]: 14 It is the submode that 32-bit operating systems and 16-bit protected mode operating systems operate in when running on an x86-64 CPU.[11]: 14

Real mode[edit]

Real mode is the initial mode of operation when the processor is initialized, and is a submode of legacy mode. It is backwards compatible with the original Intel 8086 and Intel 8088 processors. Real mode is primarily used today by operating system bootloaders, which are required by the architecture to configure virtual memory details before transitioning to higher modes. This mode is also used by any operating system that needs to communicate with the system firmware with a traditional BIOS-style interface.[29]

Intel 64[edit]

Intel 64 is Intel’s implementation of x86-64, used and implemented in various processors made by Intel.

History[edit]

Historically, AMD has developed and produced processors with instruction sets patterned after Intel’s original designs, but with x86-64, roles were reversed: Intel found itself in the position of adopting the ISA that AMD created as an extension to Intel’s own x86 processor line.

Intel’s project was originally codenamed Yamhill[30] (after the Yamhill River in Oregon’s Willamette Valley). After several years of denying its existence, Intel announced at the February 2004 IDF that the project was indeed underway. Intel’s chairman at the time, Craig Barrett, admitted that this was one of their worst-kept secrets.[31][32]

Intel’s name for this instruction set has changed several times. The name used at the IDF was CT[33] (presumably[original research?] for Clackamas Technology, another codename from an Oregon river); within weeks they began referring to it as IA-32e (for IA-32 extensions) and in March 2004 unveiled the «official» name EM64T (Extended Memory 64 Technology). In late 2006 Intel began instead using the name Intel 64 for its implementation, paralleling AMD’s use of the name AMD64.[34]

The first processor to implement Intel 64 was the multi-socket processor Xeon code-named Nocona in June 2004. In contrast, the initial Prescott chips (February 2004) did not enable this feature. Intel subsequently began selling Intel 64-enabled Pentium 4s using the E0 revision of the Prescott core, being sold on the OEM market as the Pentium 4, model F. The E0 revision also adds eXecute Disable (XD) (Intel’s name for the NX bit) to Intel 64, and has been included in then current Xeon code-named Irwindale. Intel’s official launch of Intel 64 (under the name EM64T at that time) in mainstream desktop processors was the N0 stepping Prescott-2M.

The first Intel mobile processor implementing Intel 64 is the Merom version of the Core 2 processor, which was released on July 27, 2006. None of Intel’s earlier notebook CPUs (Core Duo, Pentium M, Celeron M, Mobile Pentium 4) implement Intel 64.

Implementations[edit]

Intel’s processors implementing the Intel64 architecture include the Pentium 4 F-series/5×1 series, 506, and 516, Celeron D models 3×1, 3×6, 355, 347, 352, 360, and 365 and all later Celerons, all models of Xeon since «Nocona», all models of Pentium Dual-Core processors since «Merom-2M», the Atom 230, 330, D410, D425, D510, D525, N450, N455, N470, N475, N550, N570, N2600 and N2800, all versions of the Pentium D, Pentium Extreme Edition, Core 2, Core i9, Core i7, Core i5, and Core i3 processors, and the Xeon Phi 7200 series processors.

x86-S[edit]

x86-S is a planned simplification of Intel 64 announced in May 2023.[35] The new architecture would remove support for 16-bit and 32-bit operating systems, while 32-bit programs will still run under a 64-bit OS. A CPU would no longer have legacy mode, and start directly in 64-bit long mode. There will be a way to switch to 5-level paging without going through the unpaged mode. Specific removed features include:[36]

- Segmentation gates

- 32-bit ring 0

- VT-x will no longer emulate this feature

- Rings 1 and 2

- Ring 3 I/O port (IN/OUT) access; see port-mapped I/O

- String port I/O (INS/OUTS)

- Real mode (including huge real mode), 16-bit protected mode, VM86

- 16-bit addressing mode

- VT-x will no longer provide unrestricted mode

- 8259 support; the only APIC supported would be X2APIC

- Some unused operating system mode bits

Intel believes the change follows logically after the removal of A20 gate in 2008 and the ceasing of 16-bit and 32-bit OS support in Intel firmware in 2020. Support for legacy operating systems would be accomplished via hardware-accelerated virtualization.[36]

VIA’s x86-64 implementation[edit]

VIA Technologies introduced their first implementation of the x86-64 architecture in 2008 after five years of development by its CPU division, Centaur Technology.[37]

Codenamed «Isaiah», the 64-bit architecture was unveiled on January 24, 2008,[38] and launched on May 29 under the VIA Nano brand name.[39]

The processor supports a number of VIA-specific x86 extensions designed to boost efficiency in low-power appliances.

It is expected that the Isaiah architecture will be twice as fast in integer performance and four times as fast in floating-point performance as the previous-generation VIA Esther at an equivalent clock speed. Power consumption is also expected to be on par with the previous-generation VIA CPUs, with thermal design power ranging from 5 W to 25 W.[40]

Being a completely new design, the Isaiah architecture was built with support for features like the x86-64 instruction set and x86 virtualization which were unavailable on its predecessors, the VIA C7 line, while retaining their encryption extensions.

Microarchitecture levels[edit]

In 2020, through a collaboration between AMD, Intel, Red Hat, and SUSE, three microarchitecture levels on top of the x86-64 baseline were defined: x86-64-v2, x86-64-v3, and x86-64-v4.[41][42] These levels define specific features that can be targeted by programmers to provide compile-time optimizations. The features exposed by each level are as follows:[43]

| Level | CPU features | Example instruction |

|---|---|---|

| x86-64 (also x86-64-v1) (baseline: all x86-64 CPUs) |

CMOV | cmov |

| CX8 | cmpxchg8b | |

| FPU | fld | |

| FXSR | fxsave | |

| MMX | emms | |

| OSFXSR | fxsave | |

| SCE | syscall | |

| SSE | cvtss2si | |

| SSE2 | cvtpi2pd | |

| x86-64-v2 (circa 2009: Nehalem and Jaguar) Also:

|

CMPXCHG16B | cmpxchg16b |

| LAHF-SAHF | lahf | |

| POPCNT | popcnt | |

| SSE3 | addsubpd | |

| SSE4_1 | blendpd | |

| SSE4_2 | pcmpestri | |

| SSSE3 | phaddd | |

| x86-64-v3 (circa 2015: Haswell and Excavator) Also:

|

AVX | vzeroall |

| AVX2 | vpermd | |

| BMI1 | andn | |

| BMI2 | bzhi | |

| F16C | vcvtph2ps | |

| FMA | vfmadd132pd | |

| LZCNT | lzcnt | |

| MOVBE | movbe | |

| OSXSAVE | xgetbv | |

| x86-64-v4 (AVX-512’s general-purpose subset)

|

AVX512F | kmovw |

| AVX512BW | vdbpsadbw | |

| AVX512CD | vplzcntd | |

| AVX512DQ | vpmullq | |

| AVX512VL | — |

All levels include features found in the previous levels. Instruction set extensions not concerned with general-purpose computation, including AES-NI and RDRAND, are excluded from the level requirements.

Differences between AMD64 and Intel 64[edit]

Although nearly identical, there are some differences between the two instruction sets in the semantics of a few seldom used machine instructions (or situations), which are mainly used for system programming.[46] Compilers generally produce executables (i.e. machine code) that avoid any differences, at least for ordinary application programs. This is therefore of interest mainly to developers of compilers, operating systems and similar, which must deal with individual and special system instructions.

Recent implementations[edit]

- Intel 64’s

BSFandBSRinstructions act differently than AMD64’s when the source is zero and the operand size is 32 bits. The processor sets the zero flag and leaves the upper 32 bits of the destination undefined.[citation needed] Note that Intel documents that the destination register has an undefined value in this case, but in practice in silicon implements the same behaviour as AMD (destination unmodified). The separate claim about maybe not preserving bits in the upper 32 has not been verified, but has only been ruled out for Core 2 and Skylake,[47] not all Intel microarchitectures like 64-bit Pentium 4 or low-power Atom. - AMD64 requires a different microcode update format and control MSRs (model-specific registers), while Intel 64 implements microcode update unchanged from their 32-bit only processors.

- Intel 64 lacks some MSRs that are considered architectural in AMD64. These include

SYSCFG,TOP_MEM, andTOP_MEM2. - Intel 64 allows

SYSCALL/SYSRETonly in 64-bit mode (not in compatibility mode),[48] and allowsSYSENTER/SYSEXITin both modes.[49] AMD64 lacksSYSENTER/SYSEXITin both sub-modes of long mode.[11]: 33 - In 64-bit mode, near branches with the 66H (operand size override) prefix behave differently. Intel 64 ignores this prefix: the instruction has a 32-bit sign extended offset, and instruction pointer is not truncated. AMD64 uses a 16-bit offset field in the instruction, and clears the top 48 bits of instruction pointer.

- On Intel 64 but not AMD64, the

REX.Wprefix can be used with the far-pointer instructions (LFS,LGS,LSS,JMP FAR,CALL FAR) to increase the size of their far pointer argument to 80 bits (64-bit offset + 16-bit segment). - AMD processors raise a floating-point Invalid Exception when performing an

FLDorFSTPof an 80-bit signalling NaN, while Intel processors do not.[citation needed] - Intel 64 lacks the ability to save and restore a reduced (and thus faster) version of the floating-point state (involving the

FXSAVEandFXRSTORinstructions).[clarification needed] - AMD processors ever since Opteron Rev. E and Athlon 64 Rev. D have reintroduced limited support for segmentation, via the Long Mode Segment Limit Enable (LMSLE) bit, to ease virtualization of 64-bit guests.[50][51]

- When returning to a non-canonical address using

SYSRET, AMD64 processors execute the general protection fault handler in privilege level 3,[52] while on Intel 64 processors it is executed in privilege level 0.[53]

Older implementations[edit]

|

|

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: future tense relating to processors that have been out for years, dates with day and month but no year. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (January 2023) |

- The AMD64 processors prior to Revision F[54] (distinguished by the switch from DDR to DDR2 memory and new sockets AM2, F and S1) of 2006 lacked the

CMPXCHG16Binstruction, which is an extension of theCMPXCHG8Binstruction present on most post-80486 processors. Similar toCMPXCHG8B,CMPXCHG16Ballows for atomic operations on octa-words (128-bit values). This is useful for parallel algorithms that use compare and swap on data larger than the size of a pointer, common in lock-free and wait-free algorithms. WithoutCMPXCHG16Bone must use workarounds, such as a critical section or alternative lock-free approaches.[55] Its absence also prevents 64-bit Windows prior to Windows 8.1 from having a user-mode address space larger than 8 TB.[56] The 64-bit version of Windows 8.1 requires the instruction.[57] - Early AMD64 and Intel 64 CPUs lacked

LAHFandSAHFinstructions in 64-bit mode. AMD introduced these instructions (also in 64-bit mode) with their 90 nm (revision D) processors, starting with Athlon 64 in October 2004.[58][59] Intel introduced the instructions in October 2005 with the 0F47h and later revisions of NetBurst.[65] The 64-bit version of Windows 8.1 requires this feature.[57] - Early Intel CPUs with Intel 64 also lack the NX bit of the AMD64 architecture. It was added in the stepping E0 (0F41h) Pentium 4 in October 2004.[66] This feature is required by all versions of Windows 8.

- Early Intel 64 implementations had a 36-bit (64 GB) physical addressing of memory while original AMD64 implementations had a 40-bit (1 TB) physical addressing. Intel used the 40-bit physical addressing first on Xeon MP (Potomac), launched on 29 March 2005.[67] The difference is not a difference of the user-visible ISAs. In 2007 AMD 10h-based Opteron was the first to provide a 48-bit (256 TB) physical address space.[68][69] Intel 64’s physical addressing was extended to 44 bits (16 TB) in Nehalem-EX in 2010[70] and to 46 bits (64 TB) in Sandy Bridge E in 2011.[71][72] With the Ice Lake 3rd gen Xeon Scalable processors, Intel increased the virtual addressing to 57 bits (128 PB) and physical to 52 bits (4 PB) in 2021, necessitating a 5-level paging.[73] The following year AMD64 added the same in 4th generation EPYC (Genoa).[74] Non-server CPUs retain smaller address spaces for longer.

Adoption[edit]

In supercomputers tracked by TOP500, the appearance of 64-bit extensions for the x86 architecture enabled 64-bit x86 processors by AMD and Intel to replace most RISC processor architectures previously used in such systems (including PA-RISC, SPARC, Alpha and others), as well as 32-bit x86, even though Intel itself initially tried unsuccessfully to replace x86 with a new incompatible 64-bit architecture in the Itanium processor.

As of 2020, a Fujitsu A64FX-based supercomputer called Fugaku is number one. The first ARM-based supercomputer appeared on the list in 2018[76] and, in recent years, non-CPU architecture co-processors (GPGPU) have also played a big role in performance. Intel’s Xeon Phi «Knights Corner» coprocessors, which implement a subset of x86-64 with some vector extensions,[77] are also used, along with x86-64 processors, in the Tianhe-2 supercomputer.[78]

Operating system compatibility and characteristics[edit]

The following operating systems and releases support the x86-64 architecture in long mode.

BSD[edit]

DragonFly BSD[edit]

Preliminary infrastructure work was started in February 2004 for a x86-64 port.[79] This development later stalled. Development started again during July 2007[80]

and continued during Google Summer of Code 2008 and SoC 2009.[81][82] The first official release to contain x86-64 support was version 2.4.[83]

FreeBSD[edit]

FreeBSD first added x86-64 support under the name «amd64» as an experimental architecture in 5.1-RELEASE in June 2003. It was included as a standard distribution architecture as of 5.2-RELEASE in January 2004. Since then, FreeBSD has designated it as a Tier 1 platform. The 6.0-RELEASE version cleaned up some quirks with running x86 executables under amd64, and most drivers work just as they do on the x86 architecture. Work is currently being done to integrate more fully the x86 application binary interface (ABI), in the same manner as the Linux 32-bit ABI compatibility currently works.

NetBSD[edit]

x86-64 architecture support was first committed to the NetBSD source tree on June 19, 2001. As of NetBSD 2.0, released on December 9, 2004, NetBSD/amd64 is a fully integrated and supported port.

32-bit code is still supported in 64-bit mode, with a netbsd-32 kernel compatibility layer for 32-bit syscalls. The NX bit is used to provide non-executable stack and heap with per-page granularity (segment granularity being used on 32-bit x86).

OpenBSD[edit]

OpenBSD has supported AMD64 since OpenBSD 3.5, released on May 1, 2004. Complete in-tree implementation of AMD64 support was achieved prior to the hardware’s initial release because AMD had loaned several machines for the project’s hackathon that year. OpenBSD developers have taken to the platform because of its support for the NX bit, which allowed for an easy implementation of the W^X feature.

The code for the AMD64 port of OpenBSD also runs on Intel 64 processors which contains cloned use of the AMD64 extensions, but since Intel left out the page table NX bit in early Intel 64 processors, there is no W^X capability on those Intel CPUs; later Intel 64 processors added the NX bit under the name «XD bit». Symmetric multiprocessing (SMP) works on OpenBSD’s AMD64 port, starting with release 3.6 on November 1, 2004.

DOS[edit]

It is possible to enter long mode under DOS without a DOS extender,[84] but the user must return to real mode in order to call BIOS or DOS interrupts.

It may also be possible to enter long mode with a DOS extender similar to DOS/4GW, but more complex since x86-64 lacks virtual 8086 mode. DOS itself is not aware of that, and no benefits should be expected unless running DOS in an emulation with an adequate virtualization driver backend, for example: the mass storage interface.

Linux[edit]

Linux was the first operating system kernel to run the x86-64 architecture in long mode, starting with the 2.4 version in 2001 (preceding the hardware’s availability).[85][86] Linux also provides backward compatibility for running 32-bit executables. This permits programs to be recompiled into long mode while retaining the use of 32-bit programs. Current Linux distributions ship with x86-64-native kernels and userlands. Some, such as Arch Linux,[87] SUSE, Mandriva, and Debian, allow users to install a set of 32-bit components and libraries when installing off a 64-bit distribution medium, thus allowing most existing 32-bit applications to run alongside the 64-bit OS.

x32 ABI (Application Binary Interface), introduced in Linux 3.4, allows programs compiled for the x32 ABI to run in the 64-bit mode of x86-64 while only using 32-bit pointers and data fields.[88][89][90]

Though this limits the program to a virtual address space of 4 GB it also decreases the memory footprint of the program and in some cases can allow it to run faster.[88][89][90]

64-bit Linux allows up to 128 TB of virtual address space for individual processes, and can address approximately 64 TB of physical memory, subject to processor and system limitations.[91]

macOS[edit]

Mac OS X 10.4.7 and higher versions of Mac OS X 10.4 run 64-bit command-line tools using the POSIX and math libraries on 64-bit Intel-based machines, just as all versions of Mac OS X 10.4 and 10.5 run them on 64-bit PowerPC machines. No other libraries or frameworks work with 64-bit applications in Mac OS X 10.4.[92]

The kernel, and all kernel extensions, are 32-bit only.

Mac OS X 10.5 supports 64-bit GUI applications using Cocoa, Quartz, OpenGL, and X11 on 64-bit Intel-based machines, as well as on 64-bit PowerPC machines.[93]

All non-GUI libraries and frameworks also support 64-bit applications on those platforms. The kernel, and all kernel extensions, are 32-bit only.

Mac OS X 10.6 is the first version of macOS that supports a 64-bit kernel. However, not all 64-bit computers can run the 64-bit kernel, and not all 64-bit computers that can run the 64-bit kernel will do so by default.[94]

The 64-bit kernel, like the 32-bit kernel, supports 32-bit applications; both kernels also support 64-bit applications. 32-bit applications have a virtual address space limit of 4 GB under either kernel.[95][96] The 64-bit kernel does not support 32-bit kernel extensions, and the 32-bit kernel does not support 64-bit kernel extensions.

OS X 10.8 includes only the 64-bit kernel, but continues to support 32-bit applications; it does not support 32-bit kernel extensions, however.

macOS 10.15 includes only the 64-bit kernel and no longer supports 32-bit applications. This removal of support has presented a problem for WineHQ (and the commercial version CrossOver), as it needs to still be able to run 32-bit Windows applications. The solution, termed wine32on64, was to add thunks that bring the CPU in and out of 32-bit compatibility mode in the nominally 64-bit application.[97][98]

macOS uses the universal binary format to package 32- and 64-bit versions of application and library code into a single file; the most appropriate version is automatically selected at load time. In Mac OS X 10.6, the universal binary format is also used for the kernel and for those kernel extensions that support both 32-bit and 64-bit kernels.

Solaris[edit]

Solaris 10 and later releases support the x86-64 architecture.

For Solaris 10, just as with the SPARC architecture, there is only one operating system image, which contains a 32-bit kernel and a 64-bit kernel; this is labeled as the «x64/x86» DVD-ROM image. The default behavior is to boot a 64-bit kernel, allowing both 64-bit and existing or new 32-bit executables to be run. A 32-bit kernel can also be manually selected, in which case only 32-bit executables will run. The isainfo command can be used to determine if a system is running a 64-bit kernel.

For Solaris 11, only the 64-bit kernel is provided. However, the 64-bit kernel supports both 32- and 64-bit executables, libraries, and system calls.

Windows[edit]

x64 editions of Microsoft Windows client and server—Windows XP Professional x64 Edition and Windows Server 2003 x64 Edition—were released in March 2005.[99] Internally they are actually the same build (5.2.3790.1830 SP1),[100][101] as they share the same source base and operating system binaries, so even system updates are released in unified packages, much in the manner as Windows 2000 Professional and Server editions for x86. Windows Vista, which also has many different editions, was released in January 2007. Windows 7 was released in July 2009. Windows Server 2008 R2 was sold in only x64 and Itanium editions; later versions of Windows Server only offer an x64 edition.

Versions of Windows for x64 prior to Windows 8.1 and Windows Server 2012 R2 offer the following:

- 8 TB of virtual address space per process, accessible from both user mode and kernel mode, referred to as the user mode address space. An x64 program can use all of this, subject to backing store limits on the system, and provided it is linked with the «large address aware» option, which is present by default.[102] This is a 4096-fold increase over the default 2 GB user-mode virtual address space offered by 32-bit Windows.[103][104]

- 8 TB of kernel mode virtual address space for the operating system.[103] As with the user mode address space, this is a 4096-fold increase over 32-bit Windows versions. The increased space primarily benefits the file system cache and kernel mode «heaps» (non-paged pool and paged pool). Windows only uses a total of 16 TB out of the 256 TB implemented by the processors because early AMD64 processors lacked a

CMPXCHG16Binstruction.[105]

Under Windows 8.1 and Windows Server 2012 R2, both user mode and kernel mode virtual address spaces have been extended to 128 TB.[22] These versions of Windows will not install on processors that lack the CMPXCHG16B instruction.

The following additional characteristics apply to all x64 versions of Windows:

- Ability to run existing 32-bit applications (

.exeprograms) and dynamic link libraries (.dlls) using WoW64 if WoW64 is supported on that version. Furthermore, a 32-bit program, if it was linked with the «large address aware» option,[102] can use up to 4 GB of virtual address space in 64-bit Windows, instead of the default 2 GB (optional 3 GB with/3GBboot option and «large address aware» link option) offered by 32-bit Windows.[106] Unlike the use of the/3GBboot option on x86, this does not reduce the kernel mode virtual address space available to the operating system. 32-bit applications can, therefore, benefit from running on x64 Windows even if they are not recompiled for x86-64. - Both 32- and 64-bit applications, if not linked with «large address aware», are limited to 2 GB of virtual address space.

- Ability to use up to 128 GB (Windows XP/Vista), 192 GB (Windows 7), 512 GB (Windows 8), 1 TB (Windows Server 2003), 2 TB (Windows Server 2008/Windows 10), 4 TB (Windows Server 2012), or 24 TB (Windows Server 2016/2019) of physical random access memory (RAM).[107]

- LLP64 data model: in C/C++, «int» and «long» types are 32 bits wide, «long long» is 64 bits, while pointers and types derived from pointers are 64 bits wide.

- Kernel mode device drivers must be 64-bit versions; there is no way to run 32-bit kernel mode executables within the 64-bit operating system. User mode device drivers can be either 32-bit or 64-bit.

- 16-bit Windows (Win16) and DOS applications will not run on x86-64 versions of Windows due to the removal of the virtual DOS machine subsystem (NTVDM) which relied upon the ability to use virtual 8086 mode. Virtual 8086 mode cannot be entered while running in long mode.

- Full implementation of the NX (No Execute) page protection feature. This is also implemented on recent 32-bit versions of Windows when they are started in PAE mode.

- Instead of FS segment descriptor on x86 versions of the Windows NT family, GS segment descriptor is used to point to two operating system defined structures: Thread Information Block (NT_TIB) in user mode and Processor Control Region (KPCR) in kernel mode. Thus, for example, in user mode

GS:0is the address of the first member of the Thread Information Block. Maintaining this convention made the x86-64 port easier, but required AMD to retain the function of the FS and GS segments in long mode – even though segmented addressing per se is not really used by any modern operating system.[103] - Early reports claimed that the operating system scheduler would not save and restore the x87 FPU machine state across thread context switches. Observed behavior shows that this is not the case: the x87 state is saved and restored, except for kernel mode-only threads (a limitation that exists in the 32-bit version as well). The most recent documentation available from Microsoft states that the x87/MMX/3DNow! instructions may be used in long mode, but that they are deprecated and may cause compatibility problems in the future.[106] (3DNow! is no longer available on AMD processors, with the exception of the

PREFETCHandPREFETCHWinstructions,[108] which are also supported on Intel processors as of Broadwell.) - Some components like Jet Database Engine and Data Access Objects will not be ported to 64-bit architectures such as x86-64 and IA-64.[109][110][111]

- Microsoft Visual Studio can compile native applications to target either the x86-64 architecture, which can run only on 64-bit Microsoft Windows, or the IA-32 architecture, which can run as a 32-bit application on 32-bit Microsoft Windows or 64-bit Microsoft Windows in WoW64 emulation mode. Managed applications can be compiled either in IA-32, x86-64 or AnyCPU modes. Software created in the first two modes behave like their IA-32 or x86-64 native code counterparts respectively; When using the AnyCPU mode, however, applications in 32-bit versions of Microsoft Windows run as 32-bit applications, while they run as a 64-bit application in 64-bit editions of Microsoft Windows.

Video game consoles[edit]

Both the PlayStation 4 and Xbox One, and all variants of those consoles, incorporate AMD x86-64 processors, based on the Jaguar microarchitecture.[112][113] Firmware and games are written in x86-64 code; no legacy x86 code is involved.

The current generation, the PlayStation 5 and the Xbox Series X and Series S respectively, also incorporate AMD x86-64 processors, based on the Zen 2 microarchitecture.[114][115]

Although considered a PC, the Steam Deck uses a custom AMD x86-64 accelerated processing unit (APU), based on the Zen 2 microarchitecture.[116]

Industry naming conventions[edit]

Since AMD64 and Intel 64 are substantially similar, many software and hardware products use one vendor-neutral term to indicate their compatibility with both implementations. AMD’s original designation for this processor architecture, «x86-64», is still used for this purpose,[2] as is the variant «x86_64».[3][4] Other companies, such as Microsoft[6] and Sun Microsystems/Oracle Corporation,[5] use the contraction «x64» in marketing material.

The term IA-64 refers to the Itanium processor, and should not be confused with x86-64, as it is a completely different instruction set.

Many operating systems and products, especially those that introduced x86-64 support prior to Intel’s entry into the market, use the term «AMD64» or «amd64» to refer to both AMD64 and Intel 64.

- amd64

- Most BSD systems such as FreeBSD, MidnightBSD, NetBSD and OpenBSD refer to both AMD64 and Intel 64 under the architecture name «amd64».

- Some Linux distributions such as Debian, Ubuntu, Gentoo Linux refer to both AMD64 and Intel 64 under the architecture name «amd64».

- Microsoft Windows’s x64 versions use the AMD64 moniker internally to designate various components which use or are compatible with this architecture. For example, the environment variable PROCESSOR_ARCHITECTURE is assigned the value «AMD64» as opposed to «x86» in 32-bit versions, and the system directory on a Windows x64 Edition installation CD-ROM is named «AMD64», in contrast to «i386» in 32-bit versions.[117]

- Sun’s Solaris’s isalist command identifies both AMD64- and Intel 64-based systems as «amd64».

- Java Development Kit (JDK): the name «amd64» is used in directory names containing x86-64 files.

- x86_64

- The Linux kernel[118] and the GNU Compiler Collection refers to 64-bit architecture as «x86_64».

- Some Linux distributions, such as Fedora, openSUSE, Arch Linux, Gentoo Linux refer to this 64-bit architecture as «x86_64».

- Apple macOS refers to 64-bit architecture as «x86-64» or «x86_64», as seen in the Terminal command

arch[3] and in their developer documentation.[2][4] - Breaking with most other BSD systems, DragonFly BSD refers to 64-bit architecture as «x86_64».

- Haiku refers to 64-bit architecture as «x86_64».

Licensing[edit]

x86-64/AMD64 was solely developed by AMD. AMD holds patents on techniques used in AMD64;[119][120][121] those patents must be licensed from AMD in order to implement AMD64. Intel entered into a cross-licensing agreement with AMD, licensing to AMD their patents on existing x86 techniques, and licensing from AMD their patents on techniques used in x86-64.[122] In 2009, AMD and Intel settled several lawsuits and cross-licensing disagreements, extending their cross-licensing agreements.[123][124][125]

See also[edit]

- AMD Generic Encapsulated Software Architecture (AGESA)

- IA-32

- x86

- Transient execution CPU vulnerability

Notes[edit]

- ^ Various names are used for the instruction set. Prior to the launch, x86-64 and x86_64 were used, while upon the release AMD named it AMD64.[1] Intel initially used the names IA-32e and EM64T before finally settling on «Intel 64» for its implementation. Some in the industry, including Apple,[2][3][4] use x86-64 and x86_64, while others, notably Sun Microsystems[5] (now Oracle Corporation) and Microsoft,[6] use x64. The BSD family of OSs and several Linux distributions[7][8] use AMD64, as does Microsoft Windows internally.[9][10]

- ^ In practice, 64-bit operating systems generally do not support 16-bit applications, although modern versions of Microsoft Windows contain a limited workaround that effectively supports 16-bit InstallShield and Microsoft ACME installers by silently substituting them with 32-bit code.[12]

- ^ The Register reported that the stepping G1 (0F49h) of Pentium 4 will sample on October 17 and ship in volume on November 14.[63] However, Intel’s document says that samples are available on September 9, whereas October 17 is the «date of first availability of post-conversion material», which Intel defines as «the projected date that a customer may expect to receive the post-conversion materials. … customers should be prepared to receive the post-converted materials on this date».[64]

References[edit]

- ^ «Debian AMD64 FAQ». Debian Wiki. Archived from the original on September 26, 2019. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- ^ a b c «x86-64 Code Model». Apple. Archived from the original on June 2, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- ^ a b c

arch(1)– Darwin and macOS General Commands Manual - ^ a b c Kevin Van Vechten (August 9, 2006). «re: Intel XNU bug report». Darwin-dev mailing list. Apple Computer. Archived from the original on February 1, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2006.

The kernel and developer tools have standardized on «x86_64» for the name of the Mach-O architecture

- ^ a b «Solaris 10 on AMD Opteron». Oracle. Archived from the original on July 25, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ a b «Microsoft 64-Bit Computing». Microsoft. Archived from the original on December 12, 2010. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ «AMD64 Port». Debian. Archived from the original on September 26, 2019. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- ^ «Gentoo/AMD64 Project». Gentoo Project. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ^ «WOW64 Implementation Details». Archived from the original on April 13, 2018. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ^ «ProcessorArchitecture Class». Archived from the original on June 3, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u AMD Corporation (December 2016). «Volume 2: System Programming» (PDF). AMD64 Architecture Programmer’s Manual. AMD Corporation. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 13, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ^ Raymond Chen (October 31, 2013). «If there is no 16-bit emulation layer in 64-bit Windows, how come certain 16-bit installers are allowed to run?». Archived from the original on July 14, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ «IBM WebSphere Application Server 64-bit Performance Demystified» (PDF). IBM Corporation. September 6, 2007. p. 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

Figures 5, 6 and 7 also show the 32-bit version of WAS runs applications at full native hardware performance on the POWER and x86-64 platforms. Unlike some 64-bit processor architectures, the POWER and x86-64 hardware does not emulate 32-bit mode. Therefore applications that do not benefit from 64-bit features can run with full performance on the 32-bit version of WebSphere running on the above mentioned 64-bit platforms.

- ^ «AMD Discloses New Technologies At Microporcessor Forum» (Press release). AMD. October 5, 1999. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ «AMD Releases x86-64 Architectural Specification; Enables Market Driven Migration to 64-Bit Computing» (Press release). AMD. August 10, 2000. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ Mauerer, W. (2010). Professional Linux kernel architecture. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ «Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual, Volume 3A: System Programming Guide, Part 1» (PDF). pp. 4–7. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 16, 2011. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ a b «BIOS and Kernel Developer’s Guide (BKDG) For AMD Family 10h Processors» (PDF). p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 18, 2016. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

Physical address space increased to 48 bits.

- ^

«Myth and facts about 64-bit Linux» (PDF). March 2, 2008. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2010. Retrieved May 30, 2010.Physical address space increased to 48 bits

- ^ Shanley, Tom (1998). Pentium Pro and Pentium II System Architecture. PC System Architecture Series (Second ed.). Addison-Wesley. p. 445. ISBN 0-201-30973-4.

- ^ Microsoft Corporation. «What is PAE, NX, and SSE2 and why does my PC need to support them to run Windows 8 ?». Archived from the original on April 11, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ a b c d «Memory Limits for Windows Releases». MSDN. Microsoft. November 16, 2013. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- ^ «5-Level Paging and 5-Level EPT» (PDF). Intel. May 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved June 17, 2017.

- ^ US patent 9858198, Larry Seiler, «64KB page system that supports 4KB page operation», published 2016-12-29, issued 2018-01-02, assigned to Intel Corp.

- ^ «Opteron 6100 Series Motherboards». Supermicro Corporation. Archived from the original on June 3, 2010. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- ^ «Supermicro XeonSolutions». Supermicro Corporation. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ «Opteron 8000 Series Motherboards». Supermicro Corporation. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ «Tyan Product Matrix». MiTEC International Corporation. Archived from the original on June 6, 2010. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ a b «From the AMI Archives: AMIBIOS 8 and the Transition to EFI». American Megatrends. September 8, 2017. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ «Intel is Continuing the Yamhill Project?». Neowin. Archived from the original on June 5, 2022. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ «Craig Barrett confirms 64 bit address extensions for Xeon. And Prescott». The Inquirer. February 17, 2004. Archived from the original on January 12, 2013. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ^ ««A Roundup of 64-Bit Computing», from internetnews.com». Archived from the original on September 25, 2012. Retrieved September 18, 2006.

- ^ Lapedus, Mark. «Intel to demo ‘CT’ 64-bit processor line at IDF». EDN. AspenCore Media. Archived from the original on May 25, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ «Intel 64 Architecture». Intel. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved June 29, 2007.

- ^ «Intel Publishes «X86-S» Specification For 64-bit Only Architecture». www.phoronix.com.

- ^ a b «Envisioning a Simplified Intel Architecture for the Future». Intel.

- ^ «VIA to launch new processor architecture in 1Q08» (subscription required). DigiTimes. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved July 25, 2007.

- ^ Stokes, Jon (January 23, 2008). «Isaiah revealed: VIA’s new low-power architecture». Ars Technica. Archived from the original on January 27, 2008. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

- ^ «VIA Launches VIA Nano Processor Family» (Press release). VIA. May 29, 2008. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ «VIA Isaiah Architecture Introduction» (PDF). VIA. January 23, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 7, 2008. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ Weimer, Florian (July 10, 2020). «New x86-64 micro-architecture levels». llvm-dev (Mailing list). Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ Weimer, Florian (January 5, 2021). «Building Red Hat Enterprise Linux 9 for the x86-64-v2 microarchitecture level». Red Hat developer blog. Archived from the original on February 20, 2022. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ^ «System V Application Binary Interface Low Level System Information». x86-64 psABI repo. January 29, 2021. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via GitLab.

- ^ «QEMU version 7.2.0 released — QEMU». www.qemu.org. Archived from the original on December 21, 2022. Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ^ «ChangeLog/7.2 — QEMU». wiki.qemu.org. Archived from the original on January 9, 2023. Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ^ Wasson, Scott (March 23, 2005). «64-bit computing in theory and practice». The Tech Report. The Tech Report. Archived from the original on March 12, 2011. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ «Discussion on Stack Overflow». March 2021. Archived from the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ «Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual Volume 2 (2A, 2B & 2C): Instruction Set Reference, A–Z» (PDF). Intel. September 2013. pp. 4–397. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ^ «Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual Volume 2 (2A, 2B & 2C): Instruction Set Reference, A-Z» (PDF). Intel. September 2013. pp. 4–400. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ^ «How retiring segmentation in AMD64 long mode broke VMware». Pagetable.com. November 9, 2006. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ «VMware and CPU Virtualization Technology» (PDF). VMware. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved September 8, 2010.

- ^ «AMD64 Architecture Programmer’s Manual Volume 3: General-Purpose and System Instructions» (PDF). AMD. May 2018. p. 419. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 20, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ «Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual Volume 2 (2A, 2B & 2C): Instruction Set Reference, A-Z» (PDF). Intel. September 2014. pp. 4–412. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ^ «Live Migration with AMD-V™ Extended Migration Technology» (PDF). developer.amd.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Maged M. Michael. «Practical Lock-Free and Wait-Free LL/SC/VL Implementations Using 64-Bit CAS» (PDF). IBM. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ^ darwou (August 20, 2004). «Why is the virtual address space 4GB anyway?». The Old New Thing. Microsoft. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ^ a b «System Requirements—Windows 8.1». Archived from the original on April 28, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

To install a 64-bit OS on a 64-bit PC, your processor needs to support CMPXCHG16b, PrefetchW, and LAHF/SAHF.

- ^ Petkov, Borislav (August 10, 2009). «Re: [PATCH v2] x86: clear incorrectly forced X86_FEATURE_LAHF_LM flag». Linux kernel mailing list. Archived from the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ «Revision Guide for AMD Athlon 64 and AMD Opteron Processors» (PDF). AMD. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 24, 2009. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- ^ «Product Change Notification 105224 — 01» (PDF). Intel. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 17, 2005.

- ^ «Intel® Pentium® D Processor 800 Sequence and Intel® Pentium® Processor Extreme Edition 840 Specification Update» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 18, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ «Intel Xeon 2.8 GHz — NE80551KG0724MM / BX80551KG2800HA». CPU-World. Archived from the original on June 28, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Smith, Tony (August 23, 2005). «Intel tweaks EM64T for full AMD64 compatibility». The Register. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ «Product Change Notification 105271 – 00» (PDF). Intel. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 17, 2005.

- ^ 0F47h debuted in the B0 stepping of Pentium D on October 21,[60][61] but 0F48h which also supports LAHF/SAHF launched on October 10 in the dual-core Xeon.[62][a]

- ^ «Product Change Notification 104101 – 00» (PDF). Intel. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2004.

- ^ «64-bit Intel® Xeon™ Processor MP with up to 8MB L3 Cache Datasheet» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 17, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ «Justin Boggs’s at Microsoft PDC 2008». p. 5. Archived from the original on November 17, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ Waldecker, Brian. «AMD Opteron Multicore Processors» (PDF). p. 13. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 13, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ «Intel® Xeon® Processor 7500 Series Datasheet, Volume 2» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 17, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ «Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual». September 2014. p. 2-21. Archived from the original on May 14, 2019.

Intel 64 architecture increases the linear address space for software to 64 bits and supports physical address space up to 46 bits.

- ^ Logan, Tom (November 14, 2011). «Intel Core i7-3960X Review». Archived from the original on March 28, 2016. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ Ye, Huaisheng. «Introduction to 5-Level Paging in 3rd Gen Intel Xeon Scalable Processors with Linux» (PDF). Lenovo. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ Kennedy, Patrick (November 10, 2022). «AMD EPYC Genoa Gaps Intel Xeon in Stunning Fashion». ServeTheHome. p. 2. Archived from the original on November 17, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ «Statistics | TOP500 Supercomputer Sites». Top500.org. Archived from the original on March 19, 2014. Retrieved March 22, 2014.

- ^ «Sublist Generator | TOP500 Supercomputer Sites». www.top500.org. Archived from the original on December 7, 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- ^ «Intel® Xeon PhiTM Coprocessor Instruction Set Architecture Reference Manual» (PDF). Intel. September 7, 2012. section B.2 Intel Xeon Phi coprocessor 64 bit Mode Limitations. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 21, 2014. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^ «Intel Powers the World’s Fastest Supercomputer, Reveals New and Future High Performance Computing Technologies». Archived from the original on June 22, 2013. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ^ «cvs commit: src/sys/amd64/amd64 genassym.c src/sys/amd64/include asm.h atomic.h bootinfo.h coredump.h cpufunc.h elf.h endian.h exec.h float.h fpu.h frame.h globaldata.h ieeefp.h limits.h lock.h md_var.h param.h pcb.h pcb_ext.h pmap.h proc.h profile.h psl.h …» Archived from the original on December 4, 2008. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- ^ «AMD64 port». Archived from the original on May 18, 2010. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- ^ «DragonFlyBSD: GoogleSoC2008». Archived from the original on April 27, 2009. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- ^ «Summer of Code accepted students». Archived from the original on September 4, 2010. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- ^ «DragonFlyBSD: release24». Archived from the original on September 23, 2009. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- ^ «Tutorial for entering protected and long mode from DOS». Archived from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- ^ Andi Kleen (June 26, 2001). «Porting Linux to x86-64». Archived from the original on September 10, 2010.

Status: The kernel, compiler, tool chain work. The kernel boots and work on simulator and is used for porting of userland and running programs

- ^ Andi Kleen. «Andi Kleen’s Page». Archived from the original on December 7, 2009. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

This was the original paper describing the Linux x86-64 kernel port back when x86-64 was only available on simulators.

- ^ «Arch64 FAQ». April 23, 2012. Archived from the original on May 14, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

You can either use the multilib packages or a i686 chroot.

- ^ a b Thorsten Leemhuis (September 13, 2011). «Kernel Log: x32 ABI gets around 64-bit drawbacks». www.h-online.com. Archived from the original on October 28, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ^ a b «x32 — a native 32-bit ABI for x86-64». linuxplumbersconf.org. Archived from the original on May 5, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ^ a b «x32-abi». Google Sites. Archived from the original on October 30, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ^ «AMD64 Port». debian.org. Archived from the original on September 26, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ^ «Apple – Mac OS X Xcode 2.4 Release Notes: Compiler Tools». Apple Inc. April 11, 2007. Archived from the original on April 22, 2009. Retrieved November 19, 2012.

- ^ «Apple – Mac OS X Leopard – Technology — 64-bit». Apple Inc. Archived from the original on January 12, 2009. Retrieved November 19, 2012.

- ^ «Mac OS X v10.6: Macs that use the 64-bit kernel». Apple Inc. Archived from the original on August 31, 2009. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- ^ John Siracusa. «Mac OS X 10.6 Snow Leopard: the Ars Technica review». Ars Technica LLC. Archived from the original on October 9, 2009. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ «Mac OS X Technology». Apple Inc. Archived from the original on March 28, 2011. Retrieved November 19, 2012.

- ^ «So We Don’t Have a Solution for Catalina…Yet». CodeWeavers Blog. Archived from the original on September 29, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Thomases, Ken (December 11, 2019). «win32 on macOS». Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ «Microsoft Raises the Speed Limit with the Availability of 64-Bit Editions of Windows Server 2003 and Windows XP Professional | News Center». news.microsoft.com. Archived from the original on February 25, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ «A description of the x64-based versions of Windows Server 2003 and of Windows XP Professional x64 Edition». Microsoft Support. Archived from the original on April 20, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ «Windows Server 2003 SP1 Administration Tools Pack». Microsoft Download Center. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ a b «/LARGEADDRESSAWARE (Handle Large Addresses)». Visual Studio 2022 Documentation – MSVC Linker Reference – MSVC Linker Options. Microsoft. Archived from the original on December 21, 2022. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

The /LARGEADDRESSAWARE option tells the linker that the application can handle addresses larger than 2 gigabytes.

- ^ a b c Matt Pietrek (May 2006). «Everything You Need To Know To Start Programming 64-Bit Windows Systems». Microsoft. Retrieved April 18, 2023.

- ^ Chris St. Amand (January 2006). «Making the Move to x64». Microsoft. Retrieved April 18, 2023.

- ^ «Behind Windows x86-64’s 44-bit Virtual Memory Addressing Limit». Archived from the original on December 23, 2008. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ^ a b «64-bit programming for Game Developers». Retrieved April 18, 2023.

- ^ «Memory Limits for Windows and Windows Server Releases». Microsoft. Retrieved April 18, 2023.

- ^ Kingsley-Hughes, Adrian (August 23, 2010). «AMD says goodbye to 3DNow! instruction set». ZDNet. Archived from the original on January 8, 2023. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ «General Porting Guidelines». Programming Guide for 64-bit Windows. Microsoft Docs. Retrieved April 18, 2023.

- ^ «Driver history for Microsoft SQL Server». Microsoft Docs. Retrieved April 18, 2023.

- ^ «Microsoft OLE DB Provider for Jet and Jet ODBC driver are available in 32-bit versions only». Office Access. Microsoft Docs. KB957570. Retrieved April 18, 2023.

- ^ Anand Lal Shimpi (May 21, 2013). «The Xbox One: Hardware Analysis & Comparison to PlayStation 4». Anandtech. Archived from the original on June 7, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ^ «The Tech Spec Test: Xbox One Vs. PlayStation 4». Game Informer. May 21, 2013. Archived from the original on June 7, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ^ «What to expect from Sony ‘PlayStation 5’ launch in November». The Indian Express. August 31, 2020. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Cutress, Dr Ian. «Hot Chips 2020 Live Blog: Microsoft Xbox Series X System Architecture (6:00pm PT)». www.anandtech.com. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Hollister, Sean (November 12, 2021). «Steam Deck: Five big things we learned from Valve’s developer summit». The Verge. Archived from the original on February 7, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ «ProcessorArchitecture Fields». Archived from the original on April 28, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2013.

- ^ «An example file from Linux 3.7.8 kernel source tree displaying the usage of the term x86_64». Archived from the original on September 23, 2005. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ^ US 6877084

- ^ US 6889312

- ^ US 6732258

- ^ «Patent Cross License Agreement Between AMD and Intel». January 1, 2001. Archived from the original on June 21, 2007. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ^ «AMD Intel Settlement Agreement». Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ Stephen Shankland and Jonathan E. Skillings (November 12, 2009). «Intel to pay AMD $1.25 billion in antitrust settlement». CNET. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ Smith, Ryan (November 12, 2009). «AMD and Intel Settle Their Differences: AMD Gets To Go Fabless». AnandTech. Archived from the original on May 13, 2010.

External links[edit]

- AMD Developer Guides, Manuals & ISA Documents

- x86-64: Extending the x86 architecture to 64-bits – technical talk by the architect of AMD64 (video archive), and second talk by the same speaker (video archive)

- AMD’s «Enhanced Virus Protection»

- Intel tweaks EM64T for full AMD64 compatibility

- Analyst: Intel Reverse-Engineered AMD64

- Early report of differences between Intel IA32e and AMD64

- Porting to 64-bit GNU/Linux Systems, by Andreas Jaeger from GCC Summit 2003. An excellent paper explaining almost all practical aspects for a transition from 32-bit to 64-bit.

- Intel 64 Architecture

- Intel Software Network: «64 bits»

- TurboIRC.COM tutorials, including examples of how to of enter protected and long mode the raw way from DOS

- Seven Steps of Migrating a Program to a 64-bit System

- Memory Limits for Windows Releases

Архитектура Intel x86-64

Последнее обновление: 01.07.2023

Архитектура процессоров Intel x86-64 является на сегодняшний день доминирующей архитектурой для различного рода устройств — настольных компьютеров, ноутбуков, серверов.

Семейство процессоров Intel обычно классифицируется как машина с архитектурой фон Неймана — такая машина, которая содержит три основных компонента: центральный процессор (ЦП),

память и устройства ввода/вывода (I/0). Эти три компонента связаны между собой через системную шину (состоит из шины адреса, данных и управления).

Процессор взаимодействует с памятью и устройствами ввода-вывода, передавая через адресную шину числовой адрес участка памяти или порта

устройства ввода-вывода. Через шину данных процессор, память и устройства ввода-вывода обмениваются между собой данными. Через шину управления (control bus) передаются сигналы,

которые определяют направление передачи данных (в или из памяти, а также в или из устройства ввода-вывода).

Зачем изучать ассемблер в эпоху высокоуровневых языков? Ассемблер помогает лучше понять архитектуру компьютера. Знание ассемблера может помочь при

реверс-инжениринге, анализе вирусов и прочих вредоносных программ, а также при их создании и поиске уязвимостей. В конце концов поминание работы ассемблера является важным навыком в

низкоуровневом программировании, например, при написании операционных систем и драйверов.

Архитектура x86

Архитектура x86 обозначает большое семейство процессоров как с 16-битной, так и с 32-битной архитектурой набора команд. История x86 началась

с выходом процессора Intel 8086 в 1978 году. В 1979 году выходит функционально похожий на 8086 процессор Intel 8088.

Последующие поколения этой серии процессоров получили названия 80186, 80286, 80386 и 80486, что привело к возникновению термина «x86» как сокращению для семьи процессоров. В последствии

процессоры и серии процессоров Intel, которые представляли эту архитектуру, имели совершенно другие имена, например, серии Pentium, Celeron и т.д., но они принадлежали также к этой архитектуре. Кроме компании Intel

процессоры на архитектуре x86 также выпускала компания AMD, в частности, это серии процессоров Athlon, Duron и т.д.

Процессоры 8086 и 8088 были 16-битными, несмотря на 8-битную шину данных в 8088. Регистры в этих процессорах имели разрядность 16 бит, а набор инструкций работал

с 16-битными данными. 8086 и 8088 не поддерживали многие функции современных процессоров, например, виртуальную память и уровни защиты.

Эти процессоры имели 20 адресных линий, что ограничивало размер используемой память 1 мегабайтом. Но 20-битный адрес не мог поместиться в 16-битный регистр,

поэтому для работы с адресами необходимо было использовать несколько сложную систему сегментных регистров и смещений для доступа к полному адресному пространству размером 1 МБ.

В 1985 году компания Intel выпустила процессор 80386, который был важным шагом вперед в развитии архитектуры x86. Этот процессор был

32-битным. И адреса, регистры и АЛУ также имели разрядность в 32 бита, а инструкции изначально работали с операндами размером до 32 бит.

Кроме того, он использовал

защищенный режим (protected mode), в котором был реализан многоуровневый механизм привилегий из трех уровней — от 0 до 3. Уровень 0 представлял уровень с максимальными правами и предназначался

для ядра операционной системы, тогда как уровень 3 предназначался для прикладных пользовательских программ. Уровни 1 и 2 — промежуточные. Стоит отметить, что операционные системы Windows и Linux

до сих пор реализуют только 2 уровня — 0 и 3. 80386 поддерживал память размером 4 ГБ, в которой адреса были 32-битными, а манипуляции с сегментными регистрами и смещениями больше не требовались.

Кроме того, была добавлена поддержка выгружаемой виртуальной памяти.

После этого процессоры данной архитектуры стали 32-битными.

Архитектура x86 имеет прямой порядок следования байтов (little-endian) что означает, что многобайтовые значения хранятся в памяти с младшим значащим байтом по младшему адресу и старшим значащим байтом по старшему адресу.

Архитектура х64

Архитектура х64 изначально представляла расширение процессора x86 и его набора инструкций до 64 бит. Первая специафикация этой архитектуры назвалась

AMD64 и была представлена компанией AMD в 2000 году. Первый процессор AMD64, Opteron, был выпущен в 2003 году.

Компания Intel паралелльно развивала собственную 64-разрядную архитектуру, которая называлась IA-64 и которая была несовместима с х86. Результатом развития этой архитектуры стал процессор Itanium, который вышел в 2001 году. Однако затем